ArchLab & Jain – NSF Award

Graduate student Pranjali Jain’s research leads to $1.6 million National Science Foundation grant to explore a greener future for computer hardware

From the RMCOE News article "UCSB Researchers Receive Award to Study Sustainable Computer System Design"

When cell phones, laptops, printers, and processors reach the end of their useful lives, they get sent off to be recycled. What’s left turns into e-waste — and, for many in developed nations, that means the issue seems to disappear. But what really happens to the 62 billion kilograms of technology that get discarded each year? UC Santa Barbara third-year computer science PhD student Pranjali Jain wanted to find out. In particular, she wanted to know more about the environmental impact of e-waste, with an eye toward designing electronics that are more sustainable throughout their lifecycle.

But as she and her advisor, computer science professor and dean of the College of Creative Studies, Tim Sherwood, began looking into this question, they realized that despite the size of the problem, “there is absolutely no data out there about this,” Jain said. “There are no metrics about what components of electronics are the problem — at least not metrics that are going to be understandable to people who design and build computers.”

Now, Jain’s project has become a multidisciplinary research effort that recently received the National Science Foundation (NSF) award.

“We're really delighted to have the support from the National Science Foundation. That is transformative for this truly interdisciplinary project,” said Sherwood, who is one of the grant’s principal investigators, along with associate dean for research and director of the Materials Research Laboratory Ram Seshadri and computer science professor Jonathan Balkind. “And I'm really delighted for Pranjali to see that what began as her project is being recognized at this national level.”

This research also aligns closely with the mission of the university’s world-renowned Institute for Energy Efficiency (IEE), which all three principal investigators are already affiliated with. By uncovering the material and energy costs embedded in computer hardware, the project supports the IEE’s broader goals of promoting sustainability, reducing environmental impact, and designing more efficient, environmentally responsible systems.

“Computing is changing so much about the world,” Sherwood said. And as the world changes, there’s an important question he said researchers need to be asking: “How should we be building computers in the future to get us ready for the world we want to create together?”

Bringing E-Waste to Light

According to a recent United Nations report, the amount of e-waste generated in 2022 alone would fill 1.55 million semitrucks. Lined up end to end, these trucks would circle the entire equator. And the problem is getting worse: between 2010 and 2022, the amount of e-waste being produced nearly doubled.

Jain notes that, despite the enormous amount of e-waste, very little is known about what’s in it, particularly when it comes to computer hardware. “If you were to ask a computer scientist what materials go into making this laptop, they couldn't really tell you,” she said. “It’s not easily accessible public information. A lot of it is protected intellectual property, and companies themselves often don't really know exactly how much of which different materials go into making, for example, a laptop, because they also source the components from different manufacturers.”

It can also be difficult to make the connection between design and its ultimate destination. “I sit in my office and I write a line of code,” Balkind said. “But down the line, somebody — likely in a developing nation — is going to sit down in front of a fire pit and melt the computer to get out a valuable metal and, in the process, breathe in extremely noxious fumes.”

Starting with Servers

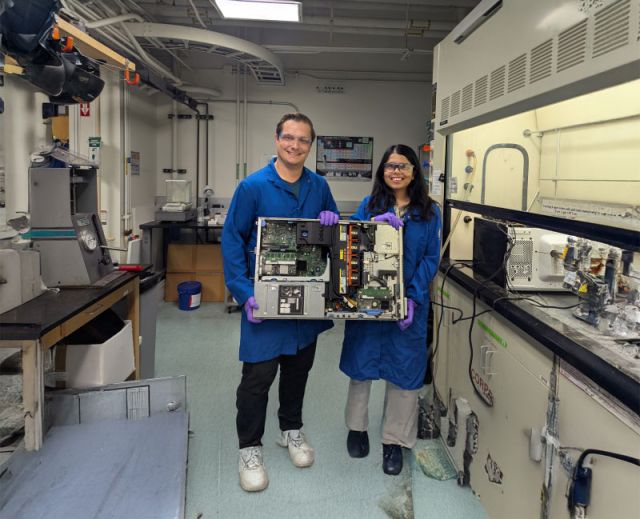

To start shedding some light on design choices that may have environmental repercussions down the line, the researchers first focused on one of the mainstays of computing: servers. Jain obtained two servers that were destined for e-waste — one from the California NanoSystems Institute at UCSB, and the other from the North Hall Data Center.

Jain and postdoctoral researcher Alex Bologna spent hours in the Materials Research Laboratory crushing the circuit boards by hand into a powder — a process which, Jain said, was satisfying but also very labor intensive. Then, they dissolved the powder in a powerful acid, and ran the samples through an inductively coupled plasma spectroscopy instrument, which allowed the researchers to quantify the metal content of the servers.

To understand more about the potential negative impacts of metals in the servers, they brought in Dingsheng Li, a professor at the University of Nevada who previously spent time as a postdoctoral researcher at UCSB’s Bren School of Environmental Science & Management. They looked at established metrics for the eco-toxicity of metals, which includes impact on both the environment and human health. They also considered how servers are typically disposed of, Jain said, making an assumption that they would be put into a landfill.

What they found was surprising: while the printed circuit boards of the servers did contain small amounts of metals known to be highly toxic — chromium, barium, nickel, and thallium — most of the toxicity came from metals like copper and aluminum that are thought to be non-toxic, Bologna said, because these common metals made up a greater proportion of the circuit board. “We can minimize the toxicity of servers simply by making them smaller and minimizing the materials used in them,” he said.

They also learned that a basic electrical component of the circuit boards, the capacitors, have an outsized impact on the boards’ toxicity. “This makes them a potential candidate for redesign or replacement for a computer architecture researcher like Pranjali,” said Bologna, who works with Sheshadri, a distinguished professor of materials and chemistry & biochemistry.

Broadening the Scope

Now, the research team plans to acquire additional e-waste to study and machines to help process it. They also intend to broaden the project’s scope beyond toxic metals. Additional metrics, such as carbon, water, and energy usage, could be incorporated to further sustainable design and production.

Balkind envisions this research perhaps leading to a dashboard that hardware designers could use to look up the downstream impacts of various design decisions. “There are all these decisions you make during your design process, and if you just had a number in front of you, it might nudge you in the right direction, whether that’s toward an improvement in the toxicity of the components, or to their cost in terms of their carbon footprint, or the water and energy used to make them,” he said.

Eventually, consumers could also have a window into the impacts of the products they buy — perhaps via a system similar to a nutrition label, that describes a product’s contents, enabling buyers to make more informed choices, he said.

Balkind hopes that providing metrics around e-waste can empower engineers, computer scientists, and others who design and build new technology. “We want to provide motivating examples, metrics, and statistics to help people understand that a small decision can have a large — and positive — impact.”